Florida Runoffs Dec. 9: Why Poll Workers Are Needed

Florida votes again Dec. 9 in Miami and Orlando. Here’s why poll workers are essential and how you can help make democracy stronger.

📌 NOTE FOR NEW READERS:

The 50501 Movement organizes peaceful action across all 50 states to defend democracy. 80,000+ subscribers strong and growing. If this resonates with you, hit subscribe for more.

The Unseen Work of Democracy

It’s 6:00 AM on an election morning. While most Americans are still asleep, thousands of citizens across the country are already at work.

Not for a paycheck, though they’ll earn one, and not for glory, though they deserve it. They’re setting up the machinery that makes democracy possible.

In a federal general election, as many as one million Americans serve as temporary election workers, what Brookings calls the “street-level bureaucrats” who transform the abstract concept of voting rights into concrete reality. They are poll workers, and without them, every promise of democracy becomes an empty one.

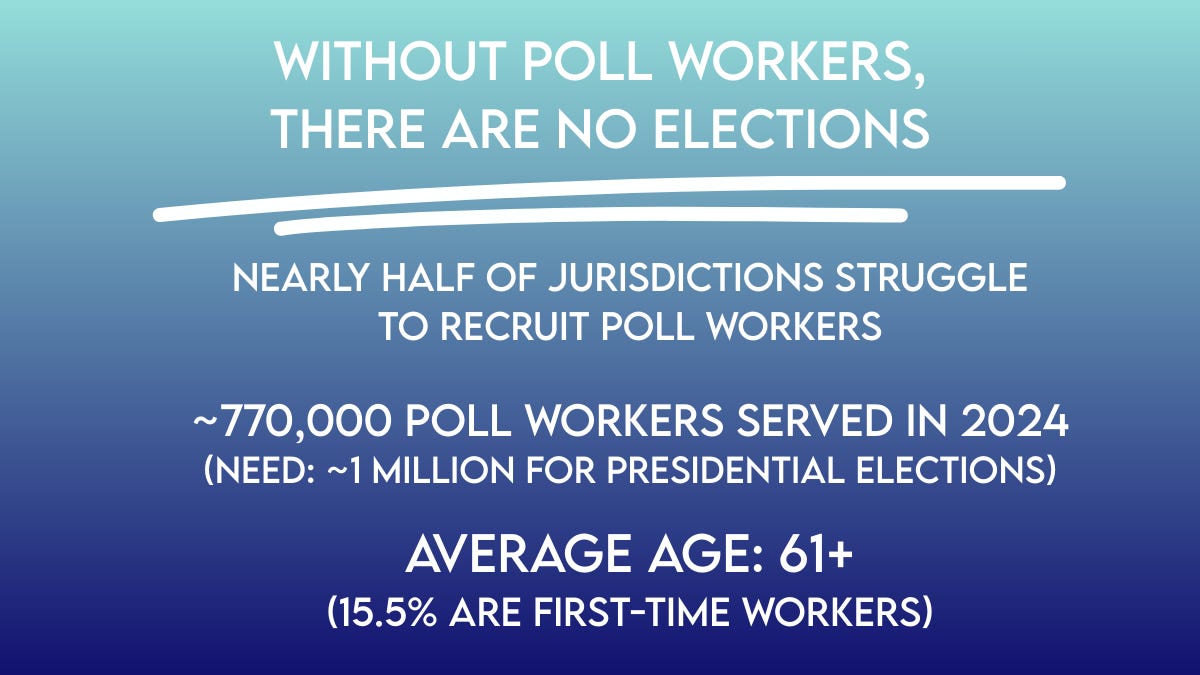

In 2024, more than 770,000 people served as poll workers nationwide.

On December 9, 2025, just two weeks away, voters in Miami and Orlando will return to the polls for critical runoff elections. Miami’s mayoral race is headed to the city’s first runoff since 2001, and Orlando’s District 3 race is also going to a runoff after a razor-thin first round. These elections will shape the future of two of Florida’s most dynamic cities.

And these elections only happen if enough poll workers show up.

*Quick note on this articles sources: the best national data on poll workers comes from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission’s Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS), which is only collected and released after each federal general election. That means there’s always a lag so even in late 2025, the most complete, nationwide poll-worker numbers come from the latest EAVS release (covering 2024, published in 2025). It’s the gold-standard dataset for staffing, recruitment, and demographics, which is why we reference it here.

THE CRISIS MOST AMERICANS DON’T KNOW EXISTS

American democracy still has a poll-worker problem. Recruitment has improved since the worst pandemic years but the shortage hasn’t vanished.

The most recent federal survey, the 2024 Election Administration and Voting Survey, shows a real shift: recruiting poll workers is getting easier than it was in 2020 and 2022. Still, just under half of jurisdictions say it’s difficult to find enough people. Easier doesn’t mean easy.

In the 2024 general election, about 772,000 Americans served as poll workers nationwide. That’s a huge civic force and it’s still not always enough for the scale of modern elections.

In 2024, most poll workers were 61 or older a generation that has carried this system for years, but can’t be asked to carry it forever.

And while new people are stepping in, the pipeline is thin: 94,466 poll workers were first-timers in 2024, about 15.5% of the workforce. We are recruiting but not fast enough to replace the ones aging out or burning out.

FLORIDA, DECEMBER 9: TWO RUNOFF ELECTIONS THAT NEED POLL WORKERS

MIAMI’S HISTORIC MAYORAL RUNOFF

Eileen Higgins and Emilio González are heading to Miami’s first mayoral runoff election since 2001.

In the November 4 election, Higgins led a 13-candidate field with about 36% of the vote (13,325 votes), while González came in second with about 19–20% (7,214 votes).

Higgins, a Miami-Dade County commissioner, has campaigned on restoring trust in City Hall, pushing government transparency, and tackling affordability and housing pressures in a city that has been rocked by repeated corruption scandals. If elected, she would be the first woman to serve as mayor of Miami.

González is a former Miami city manager (2018–2020) and a past director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services under President George W. Bush. He has the backing of Governor Ron DeSantis and is running on promises to cut property taxes and modernize city services.

The mayor’s race is officially nonpartisan, but Higgins is a registered Democrat and González a registered Republican backed by Trump, which makes this runoff a closely watched test of where the city is headed.

ORLANDO DISTRICT 3: SEPARATED BY ABOUT A DOZEN VOTES

In Orlando, Roger Chapin and Mira Tanna are also headed to a December 9 runoff after finishing separated by roughly a dozen votes in the first round.

Official results show Chapin with 2,479 votes (34.01%) and Tanna with 2,465 votes (33.82%) in a five-candidate field.

That is a very thin margin.

The runoff will determine representation for District 3 neighborhoods like College Park, Baldwin Park, Audubon Park, and parts of the North Quarter after longtime Commissioner Robert Stuart chose not to seek re-election.

Chapin, the son of former Orange County mayor Linda Chapin, was the best-funded candidate in the field and has drawn endorsements from Orlando’s political establishment. Tanna, a city grants manager, has centered her campaign on transit and walkable, bikeable neighborhoods.

Do you live in Florida? Do you know who is up for election on December 9th and what their values are? Let our community know where you stand in the comments.

WHAT RESEARCH TELLS US ABOUT POLL WORKERS

Poll workers don’t just enable voting.

They actively shape whether people trust democracy.

Democracy Fund and Reed College studied how voters’ experiences at polling places affect confidence.

They found that 60.7% of people who felt poll workers “knew the proper procedures” and also said they were “very confident” their votes had been counted as intended. That held even after controlling for age, race, gender, education, income, and vote choice.

Other election-administration research shows the same thing from another perspective:

when lines move, when the process feels orderly, and when poll workers seem prepared, voters report higher confidence.

The quality of the polling-place experience changes how legitimate an election feels to the people living through it.

And the Democracy Fund study found something even more interesting, on average, voters who said their poll workers did an “excellent job” were far less likely to lose confidence after the election than those who rated poll workers poorly.

They were 4.5 times less likely among Trump voters and 2.5 times less likely among Clinton voters to report lower confidence post-election.

In an era of declining trust in institutions, competent poll workers are one of the few proven ways to strengthen confidence in democracy.

Elections are often the single real-life touchpoint people have with our electoral system.

And poll workers are the people who make that system human.

They are the “face of elections.”

WHO BECOMES A POLL WORKER AND WHO DOESN’T

The data reveals an uncomfortable truth about who staffs American elections.

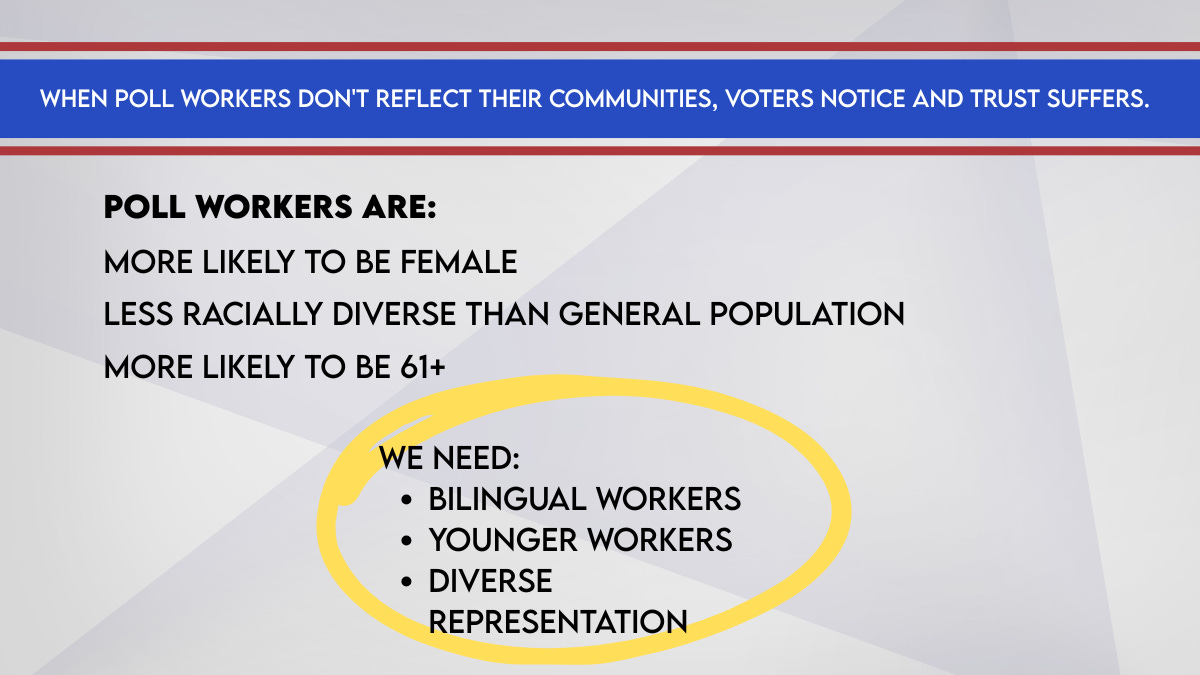

Across the U.S., poll workers skew older.

Federal EAVS data show that in recent cycles, the majority of poll workers are 61+, and jurisdictions keep warning about the “graying of the polls.”

And the stereotype exists for a reason:

poll workers are often older women, a pattern documented in election-administration research.

Research on descriptive representation in election administration shows that when voters, especially Black and Latino voters, encounter poll workers who look like them, confidence in elections rises.

When the people administering elections don’t reflect the communities they serve, trust erodes particularly in places that have already had to fight hardest for the right to vote.

Language access is part of that trust, too.

Bilingual poll workers are essential for helping voters who don’t speak English fluently navigate registration checks, ballots, and machines.

Jurisdictions covered by the Voting Rights Act must provide language assistance where it’s needed, because without it, eligible citizens can effectively be shut out of the process.

WHAT POLL WORKERS DO

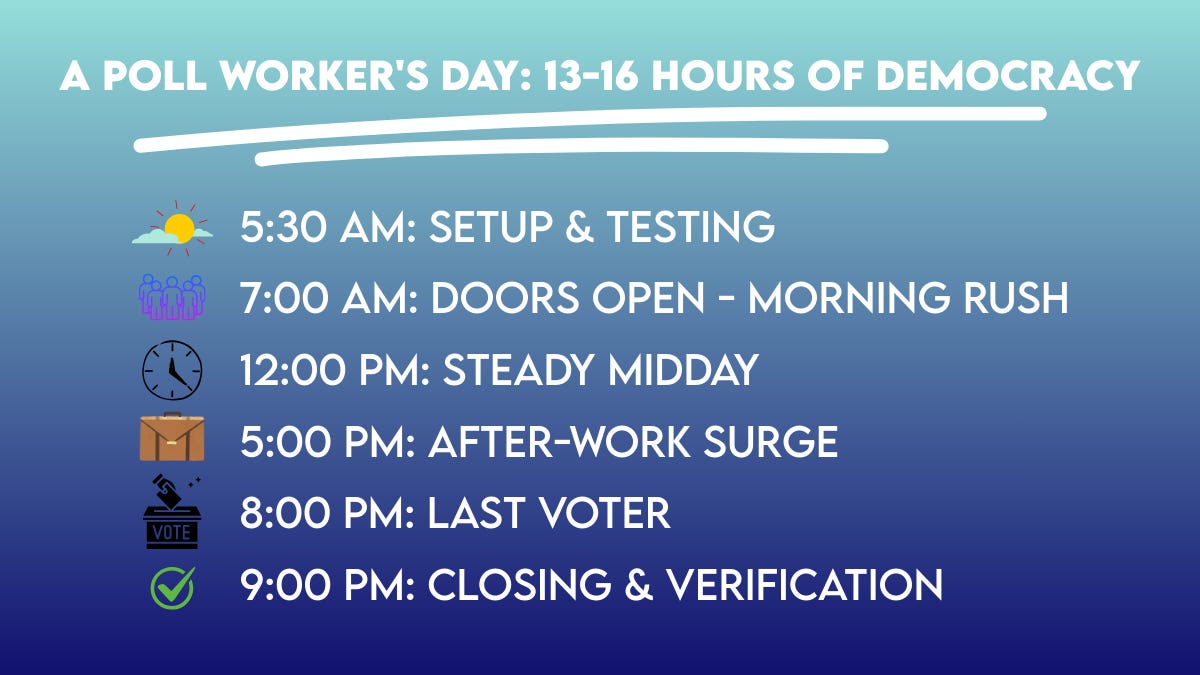

Most jurisdictions task election workers with setting up and preparing the polling location, welcoming voters, verifying voter registrations, and issuing ballots. But that clinical description doesn’t capture the reality of a 13-16 hour day that starts before dawn and ends long after polls close.

Here’s what a typical Election Day looks like:

Pre-Dawn Setup (5:30 AM - 7:00 AM) Unlock the building. Set up tables, chairs, privacy booths. Power up and test every voting machine because a single machine failure can create hours-long lines. Organize voter registration materials. Post legally required signage. Verify accessibility accommodations. Triple-check that everything is exactly where it needs to be.

Morning Rush (7:00 AM - 10:00 AM) The doors open. The voters arrive, people voting before work, elderly voters who prefer early hours, committed citizens who’ve been waiting since before opening. As required by state laws to check IDs. Verify registrations. Hand out ballots. Explain procedures. Answer questions. Keep the line moving.

Midday Steady Flow (10:00 AM - 4:00 PM) Help elderly voters. Assist voters with disabilities. Provide language assistance. Troubleshoot equipment issues. Keep detailed records. Grab food when you can.

Evening Surge (4:00 PM - 8:00 PM) The after-work rush. The line gets longer. You’ve been on your feet for 11 hours. Someone shows up at 7:59 PM and you help them vote anyway because that’s the law, democracy, and you know the importance.

Closing (8:00 PM - 9:00 PM or later) The last voter leaves. Secure all machines. Count and verify ballots. Complete detailed paperwork, paperwork that will be scrutinized if there’s any question about the election. Ensure chain of custody. Pack up. Lock up. Drive home knowing you did something truly important.

The vast majority of states require poll workers to undergo trainings, which are commonly held at the local level. Poll workers are provided with all the training they need and will be compensated for their training and service.

WHY PEOPLE BECOME POLL WORKERS

The research is pretty consistent.

People sign up for a mix of reasons:

a sense of civic duty, a desire to help their community, the social pull of working alongside neighbors, and yes, the paycheck.

But when you ask poll workers why they showed up, the first answer is almost always the same: because it felt like a civic responsibility.

That’s the “why.”

The “what keeps them coming back” is different.

Recent retention studies find that solidarity and purpose matter a lot.

The social capital of serving with others, and the feeling that the work is meaningful.

People come for civic duty, but they stay for community.

Poll workers are more likely to return when they believe their service genuinely matters, and when they feel respected, supported, and well-supported by election officials and voters alike.

And the compensation piece is real, too.

Even when civic pride is the main driver, pay can be the deciding factor especially for people who can’t afford to give up a 13–16 hour day without some support.

That’s why jurisdictions that raise stipends or hourly rates often see recruitment improve.

Poll worker pay isn’t uniform and it varies widely by state and county, and some places have increased compensation in recent years specifically to address shortages.

People serve because they love democracy and connection.

They keep serving when the community makes that love sustainable.

HOW TO BECOME A POLL WORKER

The rules vary by state and county, but the basics are straightforward.

Most jurisdictions recruit poll workers locally, typically requiring you to be a resident or a registered (or pre-registered) voter in the county where you serve. Requirements differ by state, and some places allow flexibility when shortages are severe, but local service is the norm.

A handful of states are now all-mail states including Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Utah, and Hawaii, meaning ballots are mailed automatically to every registered voter. These states rely much less on traditional precinct poll workers, though they still need election workers for ballot drop sites, voter service centers, and counting.

In most jurisdictions, you also need to be:

at least 18, and

a registered voter in your state or county (though some states allow younger “student poll workers” in certain roles).

You’ll get training through your local elections office, and you’re paid for both training and your shift.

THE HISTORICAL PARALLEL

One of the easiest mistakes to make about democracy is to think of it as something we possess like a permanent inheritance, rather than something we perform.

The right to vote can be written into law.

But the act of voting… its real, lived existence has always depended on people willing to do the quiet work that turns rights into reality.

That truth came into focus after Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

On paper, the law outlawed literacy tests and other barriers designed to keep Black Americans from the ballot box.

But laws don’t implement themselves.

The first elections under that new protection still required someone to unlock the doors. Someone to check the rolls. Someone to hand a ballot to a citizen who had been told over and over that democracy was not meant for them.

And people did.

In communities that had been excluded for generations, citizens stepped into the machinery of elections and made it function because they understood something we still need to remember:

A democracy is only as strong as the people who are willing to sustain it.

That is still true now.

We talk a lot about candidates, courts, and headlines.

But on Election Day, the first face most voters meet is not a politician’s. It’s a poll worker’s.

A neighbor.

A retiree.

A student.

A person who gets up before dawn so the rest of us can do something that should never be taken for granted.

When those people are missing, the rest of democracy hits a wall of reality.

Because poll workers are not a side detail of elections.

They are the human infrastructure that make elections possible.

In the last few federal election cycles, local officials have been clear about something most voters never see: recruiting enough poll workers has been hard.

The newest national survey, the 2024 Election Administration and Voting Survey, shows real improvement since the pandemic years. Jurisdictions report that recruiting poll workers has continued getting easier compared with 2020 and 2022.

But the problem isn’t gone. In 2024, the share of jurisdictions reporting difficulty is still under half which means tens of thousands of precincts are one bad recruitment season away from long lines, stressed staff, and avoidable chaos.

And we are already in the period where election offices are staffing up for the next cycle. Shortages don’t start on Election Day. They start months beforehand, when not enough people sign up to train.

If you can serve at the polls in your community:

Apply now.

Training and placements happen early, and elections only run if enough people are willing to help.

If you can’t serve in the next election, but you could serve in future ones:

Apply anyway. Get into the system.

The 2026 cycle is closer than it feels, and let’s not forget about local elections! Counties everywhere are already building their worker lists.

If you own a business or manage a workplace:

You have more power here than you might realize.

The EAC’s National Poll Worker Recruitment Day guidance specifically encourages employers to spread the word, recruit employees, and offer time off for poll work.

If you can, give paid leave for Election Day service. A single paid-leave policy can keep a whole polling place fully staffed on Election Day.

If you absolutely can’t serve as a poll worker:

Please don’t stop there.

Share this post with three people who could.

Recruitment moves fastest when it comes from someone people trust.

Do you have a good poll or voting story? Share it with us in the comments!

A FINAL WORD

One of the most important things to understand about elections is that they are not just a contest between candidates.

They are a test of whether a community still believes in shared rules.

And that belief doesn’t rise or fall only on speeches, or courts.

It’s in the moments at a folding table when a voter walks in unsure, and someone on the other side of that table helps them through the process with competence and care.

The Center for Civic Design calls poll workers the “face of elections,” and that’s exactly right.

You are the first representation of democracy most voters will meet.

You make the process legible, calm, and fair.

Will enough of us show up to make that vote possible?

Will you be one of them?

TAKE ACTION

1) Sign up to be a poll worker where you live.

Every county recruits poll workers through its local elections office. You don’t need special experience, just a willingness to learn and show up. Training is provided and you’re paid for your time.

Find your local office here

Click your state → your county → “Poll Workers” or “Election Workers.”

2) If your state votes mostly by mail (like Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Utah, Hawaii, etc.)

You may not staff a traditional polling place, but your election office still needs election workers for ballot drop sites, voter service centers, signature verification, and counting. The same directory above will point you to the right program.

3) If you can’t serve this next election but could serve in the future:

Apply anyway. Getting in the system early helps counties train up enough people before the rush hits.

4) If you run a business or manage a workplace:

Consider offering Election Day paid leave for employees who serve. Employer support is one of the recruitment strategies recommended by the EAC, and it can make the difference for an entire polling location.

5) If you can’t serve yourself:

Help us by sharing this post to someone who might.

Will you sign up? What’s stopping you? If you have been a poll worker before, share what it’s like and your experience!

Ive tried to be a poll worker for at least 10 years. One of the biggest issues is that you have to work the entire day. Only older retired folks have that luxury. I could manage a 4 hour shift but cannot do 8-10 hours. If they want younger folks they need to make it POSSIBLE for them to do the job. Its frustrating to me because they are desperate for help but refuse to consider what is necessary to get it. Every time I ask they tell me that its not possible, I have to be able to work the entire day. Doesn't make sense to me. I have resorted to being a poll watcher, which does accommodate working folks, parents, college students, etc.

I worked as a poll worker the last few elections and although it is a long day, it was rewarding. The training was informative and if you have doubts about the integrity of your election, you should take the training then work an election.