Economic Noncooperation

What research shows about consumer pressure, spending slowdowns, and political leverage

📌 NOTE FOR NEW READERS:

The 50501 Movement organizes peaceful action across all 50 states to defend democracy. This publication is nearly 100k readers strong and growing. If this resonates with you, hit subscribe!

TL;DR

In the United States, household consumer spending consistently accounts for roughly two-thirds of GDP, making it a central driver of economic activity and a meaningful pressure point when it changes at scale. Decades of economic research and civil-resistance scholarship show that consumer-driven pressure whether through boycotts, subscription cancellations, or broader spending slowdowns, rarely works through sudden revenue collapse, but can influence outcomes through reputational risk, investor behavior, regulatory attention, and political responsiveness, especially when sustained and coordinated. The evidence does not support the idea that isolated or short-term spending pauses alone produce systemic change, but it does support economic noncooperation as a legitimate and historically grounded tool when embedded in broader, organized campaigns with clear objectives and endurance.

Why consumer spending matters in a way that is not ideological, but structural

In modern macroeconomic terms, the centrality of consumer spending is an accounting reality.

According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Federal Reserve, personal consumption expenditures have made up approximately 65–70 percent of U.S. GDP for decades, a proportion that has remained remarkably stable across economic cycles.

This means that when economists, policymakers, and central banks assess economic health, they are largely tracking the behavior of households rather than factories or financial institutions in isolation.

This explains why contractions in consumer demand reliably trigger responses from political and economic leadership.

Research from the Federal Reserve system shows that consumption shocks play a significant role in driving recessions and recoveries, influencing business investment decisions, labor demand, and fiscal planning.

When household spending declines sharply and persistently, the effects cascade through employment, tax revenues, credit markets, and public budgets.

Consumer behavior represents a pressure point. The economy is not jjust something we live inside of; it is something we actively generate through participation.

What research on boycotts show us and why it’s often misunderstood

There is a substantial academic literature examining consumer boycotts, spanning economics, sociology, and organizational behavior.

One of the most cited findings across this research is that boycotts do not typically produce dramatic, immediate declines in a targeted company’s revenues.

This observation is often used online to dismiss boycotts entirely, but that leap does not follow from the evidence.

Scholars such as Brayden King at Northwestern University have shown that the primary impact of boycotts is rarely direct financial harm.

Instead, boycotts tend to operate by increasing reputational risk, attracting sustained media attention, and altering how investors, regulators, and political actors perceive the cost of maintaining certain behaviors.

In other words, boycotts function less like economic sieges and more like signaling mechanisms that raise the long-term risk profile of inaction.

Additional research in organizational sociology finds that companies facing sustained boycott pressure often respond with internal changes not always because sales collapse, but because executives and boards anticipate future consequences related to brand value, shareholder confidence, and regulatory exposure.

These responses may include partial concessions, changes in messaging, leadership adjustments, or behind-the-scenes lobbying shifts.

This distinction is important to understand because it reframes effectiveness.

If effectiveness is defined narrowly as “did this boycott bankrupt the company,” most boycotts will appear to fail.

If effectiveness is defined as “did this pressure alter incentives, constrain choices, or force engagement,” the record looks more mixed and more instructive.

Economic noncooperation as a category of civic action

Long before modern consumer culture, scholars of nonviolent resistance identified economic noncooperation as a distinct and recurring method of political pressure.

Gene Sharp’s widely used taxonomy of nonviolent action places boycotts, strikes, and refusal to participate in economic systems alongside protest and political noncooperation as core mechanisms through which populations exert influence without violence.

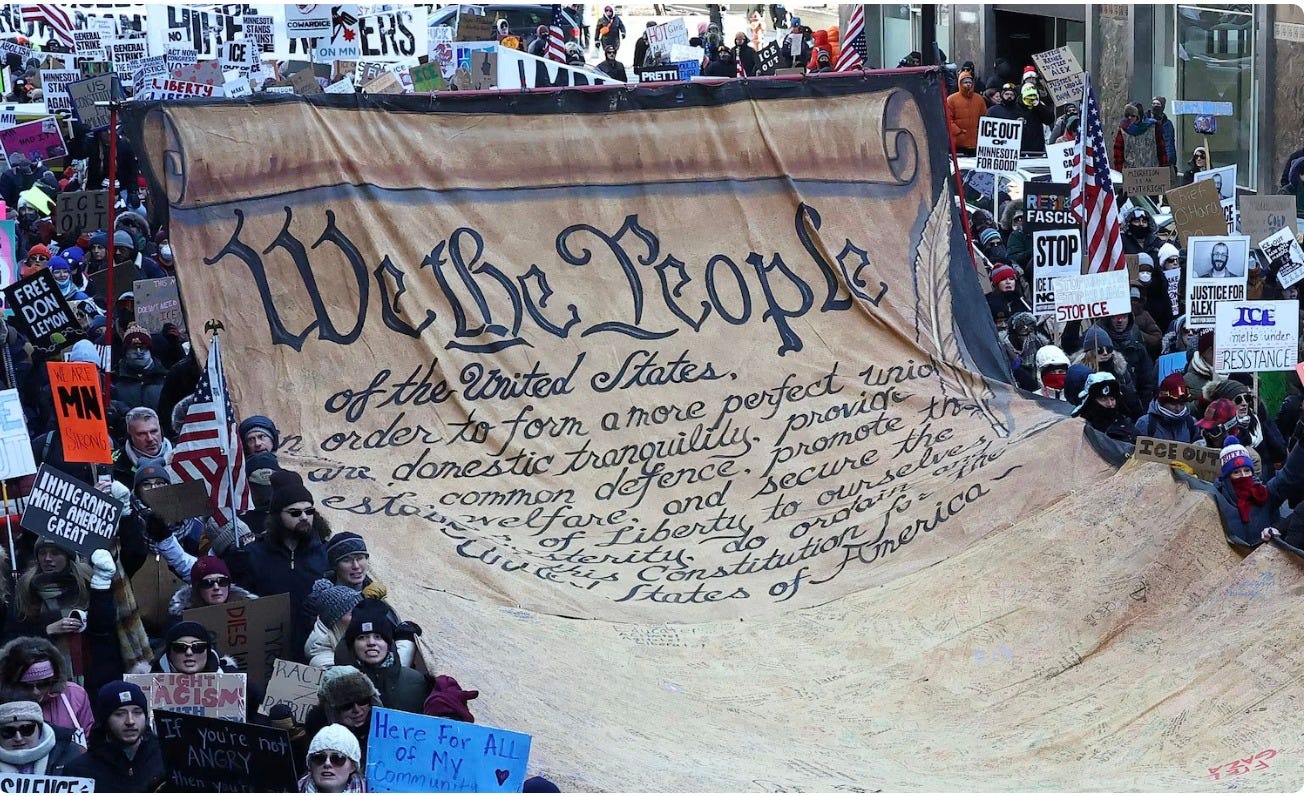

More recent empirical research on nonviolent campaigns, including work by Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, demonstrates that sustained, organized nonviolent movements have historically been more successful than violent ones in achieving political objectives.

While this research does not isolate consumer spending as a single causal factor, it situates economic withdrawal as one component of broader campaigns that combine participation, endurance, legitimacy, and scale.

The consistent finding across this literature is not that any single tactic guarantees success, but that pressure accumulates when multiple forms of noncooperation reinforce one another over time.

Why unsubscribe culture resonates and where the limits are

Calls to cancel subscriptions or reduce discretionary spending resonate with many people because they lower the barriers to participation.

Unsubscribing is simple, measurable, and relatively low-risk compared to labor strikes or civil disobedience.

From a behavioral perspective, these actions also build habits of opting out and create visible signals of discontent that can be shared publicly.

From a research standpoint, these actions align with what consumer-behavior studies show about participation thresholds that people are more likely to engage in collective action when the personal cost is manageable and the action feels legible and repeatable.

However, the evidence also suggests that such actions are most meaningful as entry points, not endpoints.

On their own, they rarely generate sufficient pressure to alter large-scale political decisions. Their value lies in normalization, coordination, and signaling… creating the conditions under which more sustained and targeted forms of pressure can develop.

Pressure points that do work

Across economic research and civil-resistance studies, several conditions consistently appear in cases where economic pressure contributes to meaningful change.

Sustained duration matters more than intensity, because decision-makers respond to signals that appear stable rather than episodic.

Reputational visibility helps more than raw participation numbers, because elite actors are highly sensitive to narratives that threaten legitimacy.

Coordination with other forms of pressure like legal challenges, electoral mobilization, regulatory scrutiny, and public discourse amplifies the effect of economic withdrawal by making inaction costly across multiple domains simultaneously.

Most importantly, successful campaigns tend to be legible.

Those in power must be able to identify what behavior is being challenged, why the pressure is being applied, and what conditions would relieve it.

Ambiguous or purely expressive actions may feel emotionally satisfying, but they are harder to translate into institutional response.

The research does not support the idea that people can just “stop spending” for a short period and expect systemic transformation. It does, however, support a more sober and defensible claim that consumer behavior is a real and measurable pressure point in modern economies, and coordinated economic noncooperation has historically contributed to political change when it is sustained, legible, and embedded within broader civic campaigns.

Economic noncooperation is a slow-building form of influence that works by reshaping incentives, expectations, and risk calculations over time. Used carelessly, it dissipates. Used strategically, it accumulates.

If economic noncooperation is best understood as a long-term pressure strategy rather than a one-time action, what forms of participation do you think are most realistic for people to sustain and what safeguards help to ensure that pressure doesn’t fall first on those with the least power?

📣 On February 17, we’re taking more action. Find your district action and get involved at citizensimpeachment.com…

Join the National In-District Lobbying Day to demand Congress hold Trump accountable and take steps toward impeachment.

Organized by Citizens’ Impeachment, FLARE USA, and 50501, this nationwide day of direct action calls on people everywhere to show up, speak out, and demand justice.

Get ready for the next No Kings mobilization set for Saturday, March 28th, with a flagship event planned for Minneapolis, Minnesota. Visit Nokings.org for more information. Updates to come.

☕ If this article earned you a coffee-level nod, there’s a button below, thank you for supporting our journalism!

Sources

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis / Federal Reserve Economic Data, Personal Consumption Expenditures as a Share of GDP

Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Consumption Shocks and the Business Cycle

St. Louis Fed, Holiday Spending: A Gift for the Economy

Brayden G. King (Northwestern University), The Effect of Corporate Boycotts

McDonnell, King & Soule, Administrative Science Quarterly, A Dynamic Process Model of Private Politics

Klein, Smith & John, Why We Boycott: Consumer Motivations for Boycott Participation

Gene Sharp, 198 Methods of Nonviolent Action

Chenoweth & Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works

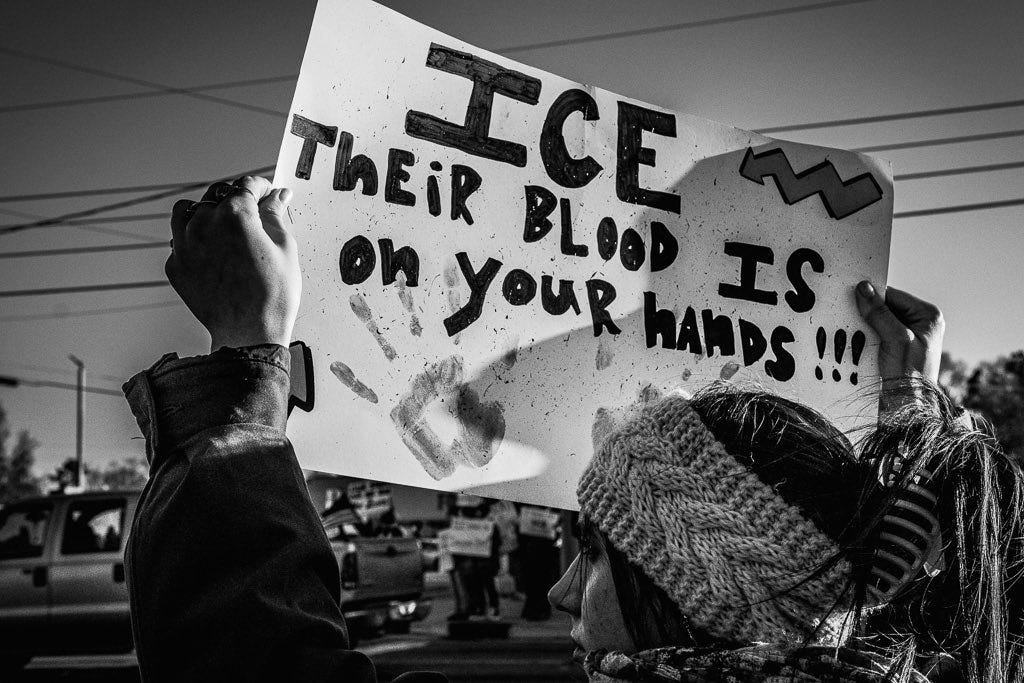

Avelo Airlines is a good example of combining a consumer boycott with public shaming including billboards (at least in New Haven) and protests in front of airports week after week. It took us awhile but we were successful. They stopped ICE Air flights ✈️ 💪 Persistence is key!

This is a terrific article - kudos! I plan to share it widely, including in a future issue of Don't Mourn Organize Eastern Mass substack. There's no byline: I'm curious who researched and wrote it.

The 2025 movements against the Trump attacks included a mix of foolish calls to economic noncooperation (e.g. one-day Amazon boycotts) and well-strategized, well-targeted pressure campaigns against Tesla, Avelo, Disney and Target. Next: Citizens Bank!

(I'm writing as Betsy Leondar-Wright, one of the editors of Don't Mourn Organize.)